Toward a safer, more reliable

engine

Mike

Stokes, Boeing Integrated Defense System manager of the Controller

Software Laboratory for the Space Shuttle Main Engine program in

Huntsville, Ala., said he and his team have been looking forward

to flying again since the day Space Shuttle Columbia was

lost. Mike

Stokes, Boeing Integrated Defense System manager of the Controller

Software Laboratory for the Space Shuttle Main Engine program in

Huntsville, Ala., said he and his team have been looking forward

to flying again since the day Space Shuttle Columbia was

lost.

Stokes and the Controller Software Laboratory team develop the

Space Shuttle Main Engine Controller software, which controls engine

operation during flight. A computer mounted on each of the three

Space Shuttle Main Engines monitors almost 90 sensors-including

engine pressures, temperatures, propellant flow rates, vibrations

and speed-as well as dozens of other engine indications, he said.

"The sensors are monitored 50 times per second for the duration

of ascent, and this information is then used to control the engine,

make assessments of its health, and take any necessary action to

keep the astronauts and orbiter safe," he added.

FULL STORY >>

Tests helping to solve riddle

of tile damage

The

vivid images of foam coming off the external tanks of Space Shuttle

Columbia during ascent reminded the world that human space

flight can be dangerous. As NASA and its team of contractors get

ready for return to flight this fall, one of their priorities is

to understand better the impact of debris on the Space Shuttle tiles. The

vivid images of foam coming off the external tanks of Space Shuttle

Columbia during ascent reminded the world that human space

flight can be dangerous. As NASA and its team of contractors get

ready for return to flight this fall, one of their priorities is

to understand better the impact of debris on the Space Shuttle tiles.

Shawn Sorenson, Boeing IDS tile-testing project engineer and coordinator,

sees the results of tile testing every day at the foam test center

at Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. One of the recommendations

of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board investigation

was to improve the capability to assess what damage debris such

as ice or insulating foam from the external tank could inflict on

the orbiter.

FULL STORY >>

Back in the Space Shuttle tile

business

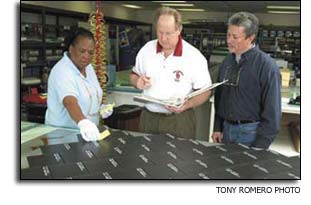

Boeing

Integrated Defense Systems employees in Palmdale, Calif., once thought

that their tile production days were over when the company decided

to move the Orbiter Maintenance and Modification process to United

Space Alliance facilities in Florida. But today, Boeing engineers

and technicians in Palmdale are back in the business of manufacturing

tiles for the Space Shuttle. Boeing

Integrated Defense Systems employees in Palmdale, Calif., once thought

that their tile production days were over when the company decided

to move the Orbiter Maintenance and Modification process to United

Space Alliance facilities in Florida. But today, Boeing engineers

and technicians in Palmdale are back in the business of manufacturing

tiles for the Space Shuttle.

That's because the loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia

and subsequent tile impact testing recommended by the Columbia Accident

Investigation Board have created a requirement for the manufacture

of large amounts of tile. In these tests, various substances, such

as foam and ice, are being shot from compressed air guns at different

angles and speeds onto new tile "targets." Structural and thermal

engineering communities are using data from the tests to improve

their damage prediction capabilities.

FULL STORY >>

Long hours searching for clues

and cracks

Dave

Lubas, Boeing Integrated Defense Systems materials and process engineer,

was at home preparing to celebrate his son's birthday on Feb. 1,

2003. He had an ear cocked for the familiar sonic boom that would

signal Space Shuttle Columbia's reentry into the atmosphere

over Florida. But the boom never came, and Lubas knew something

was wrong. A telephone call shortly after 9 a.m. confirmed his worst

suspicions: Columbia and its crew had been lost. Dave

Lubas, Boeing Integrated Defense Systems materials and process engineer,

was at home preparing to celebrate his son's birthday on Feb. 1,

2003. He had an ear cocked for the familiar sonic boom that would

signal Space Shuttle Columbia's reentry into the atmosphere

over Florida. But the boom never came, and Lubas knew something

was wrong. A telephone call shortly after 9 a.m. confirmed his worst

suspicions: Columbia and its crew had been lost.

The 12-year Boeing employee immediately volunteered to help with

debris identification. Pieces of Columbia strewn across

vast areas of Texas were being trucked into the Kennedy Space Center,

Fla. Lubas was assigned to the team that was reconstructing the

leading edge of Columbia's left wing, where investigators

believed a fatal breach permitted hot gases to enter the orbiter

at the start of the crew's re-entry.

FULL STORY >>

|